What is Spinal Stenosis?

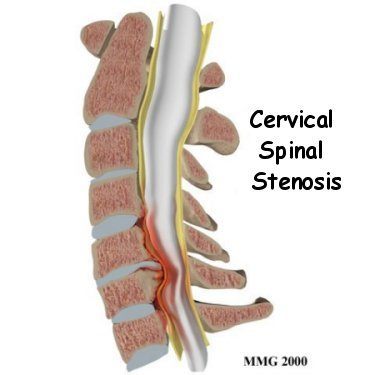

It is estimated up to 84% of adults will suffer from lower back pain during their lifetime1. Some of these cases are due to a condition termed spinal stenosis, which refers to the narrowing of any space within the spine that contains nervous tissue; such spaces include the central spinal canal, the lateral recesses just at either side of the spinal canal, and the neural foramen, or the opening through which nerve roots exit the spine2.

When this narrowing compresses nearby nerve roots, particularly in the lateral recesses and neural foramina, it can lead to a radiculopathy causing pain and potential weakness and numbness to affected extremities. Radiculopathies are most common in the cervical (neck) and lumbar (lower back) regions of the spine. If the narrowing occurs in the central canal and compresses the spinal cord, it can result in spinal cord damage, weakness, incontinence and loss of sensation which is a surgical emergency8.

Spinal Stenosis Causes

While back and/or leg pain is one of the most common complaints physicians encounter, few of these cases are actually spinal stenosis. In one study of more than 4000 patients with low back pain, 14% were diagnosed with spinal stenosis3. Spinal stenosis can be acquired or be present from a congenital birth anomaly such as dwarfism or spina bifida. The majority of cases are acquired with the narrowing caused by2:

- Degenerative arthritis (spondylosis) with age

- Forward slipping of a vertebrae (spondylolisthesis)

- Osteophyte (bone spur) formation

- Overgrowth of the ligaments connecting adjacent vertebrae

- Trauma

- An obstruction such as a tumor or cyst

- A bulged or herniated disc

- Other skeletal disease

In the aforementioned study, the stenosis was acquired in 75% of these cases, with the remaining due to congenital defects from birth or some combination of both3.

Diagnosis of Spinal Stenosis

Diagnosis of spinal stenosis can be made by a pain specialist via a comprehensive patient history, physical exam, and neurological exam with supplemental imaging.

Perhaps the best indication that lumbar spinal stenosis is present when symptoms (mainly pain) occur with walking, standing and with postural changes, but are alleviated with lying down or sitting; this is termed neurogenic claudication2. One systematic review showed these symptoms to be present in 82% of lumbar spinal stenosis cases. Pain is the most common symptom, but it is also fairly common to find symptoms of weakness, numbness, tingling or instability with walking given spinal stenosis. Symptoms usually present simultaneously on both sides of the body, but have been known to frequently effect one side over the other.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for imaging spinal stenosis, and can visualize narrowing of the spinal canal and neural foramen2. Computed tomography (CT) scans offer comparable visualization, however subject the patient to potentially unnecessary radiation; a CT scan may be indicated for some patients, however, such as those in which exposure to a magnet is not possible (due to metal surgical devices). Each imaging modality offers select advantages as well — MRI is capable of better visualizing the spinal cord and nervous tissue, while CT is better able to distinguish skeletal causes of stenosis, such as bone spurs.

While not as useful as imaging or patient history, physical exam findings can aid in the diagnosis of spinal stenosis as well. A test of balance known as a Romberg test has also been associated with lumbar spinal stenosis, and a wide-based gait is a common clinical finding6, 9.

A definitive diagnosis requires both symptoms consistent with stenosis and visualization of the narrowing with imaging technology6. Thus even if some degree of narrowing is present, without symptoms the condition will often go unnoticed without problems and does not qualify as diagnostic spinal stenosis.

Treating Spinal Stenosis

Patients diagnosed with spinal stenosis have a variety of treatment options available depending upon symptom severity and patient preference. Treatment typically begins with non-surgical pain management and posture correction but also include surgical approaches as necessary or desired. The most common non-surgical therapies include7:

- Physical therapy- used to strengthen the muscles involved in stabilizing the spine. In particular, a major goal is to prevent lordosis, or pronounced backward curvature of the lumbar spine which places horizontal strain on adjacent vertebrae effectively narrowing passageways for nervous tissue

- Life-style changes- exacerbating activity avoidance and weight loss can also help minimize strain on the spine and improve the symptoms of stenosis

- Medications- aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen (Advil™) or naproxen (Aleve™), or opiate narcotics can be used for long-term and short-term pain management respectively

Surgical intervention is an elective choice for patients after non-surgical therapies have failed to provide relief or when symptoms become disabling. Surgical intervention is a necessity with the presence of certain alarm symptoms, such as rapid onset weakness, numbness and/or incontinence of the bladder or bowel. It is critical to carefully evaluate potential surgical candidates to weigh the risks and benefits of surgery. Standard procedures include7:

- A laminectomy can be performed in patients without spondylolisthesis (forward slipping of the vertebrae) to remove a portion of vertebral bone creating more space for compressed nerves

- For patients with spondylolisthesis, spinal fusion can be performed in conjunction with a de-compressive procedure (such as a laminectomy) in order to stabilize the spinal column

- Certain patient populations may benefit from the placement of a spacer in between the spinous processes of adjacent vertebrae to relieve compression

Treatment for spinal stenosis focuses primarily on assisting patients in managing pain and retaining function. Spinal stenosis is generally a slowly progressive disorder and should be treated as such, particularly when the benefits of more aggressive therapy (such as surgery) can easily be outweighed by the side effects of treatment5.

Patient outcomes are dependent upon the severity of stenosis, and the treatment option employed. For mildly symptomatic patients, many will reap benefit from conservative management of symptoms. For those with moderate or severe spinal stenosis, surgical intervention has been shown to provide relief 75% of the time after five years3. When a primary surgery is insufficient, a secondary de-compressive surgery can also be an option4. Without treatment, spinal stenosis due to degeneration tends to remain symptomatically stagnant; one study in which patients without surgical intervention were followed for four years showed that symptoms tend to persist unchanged in 70% of cases, get better in 15% and get worse for the last 15%7.

References

- Wheeler, S.; et al. Approach to the diagnosis and evaluation of low back pain in adults. In: UpToDate, Basow, DS (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2010.

- Levin, K. Lumbar spinal stenosis: pathophysiology, clinical features and diagnosis. In: UpToDate, Basow, DS (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2011.

- Long, D.M., et al., Persistent back pain and sciatica in the United States: patient characteristics. J Spinal Disord, 1996. 9(1): p. 40-58.

- Engstrom, J., Back and Neck Pain, in Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, A. Fauci, Editor. 2008. p. 107-117.

- Matz, P.G., et al., The natural history of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine, 2009. 11(2): p. 104-11.

- Suri, P., et al., Does this older adult with lower extremity pain have the clinical syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis? JAMA, 2010. 304(23): p. 2628-36.

- Levin, K. Lumbar spinal stenosis: treatment and prognosis. In: UpToDate, Basow, DS (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2010.

- Perron, A.D., Spinal Cord Disorders, in Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, e.a. Marx, Editor. 2010, Mosby – Elsevier. p. 1389-1397.

- Katz, J.N., et al., Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Diagnostic value of the history and physical examination. Arthritis Rheum, 1995. 38(9): p. 1236-41.